| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Commander

Paul Ascher

First Admiral Staff Officer

* 18.12.1899 in Stutgarten (Brandenburg) – † 27.5.1941

|

|

|

|

Germany (1899)

Sources:

Gert † & Ursula Ascher

(Son & daughter-in-law) / Hamburg

Monika Krestas (daughter)

www.maritimequest.com

W. Lohmann u. H.H. Hildebrand: Die deutsche Kriegsmarine 1939 – 1945, Band III

|

Paul Ascher was born on December 18, 1899 on the Stutgarten estate in Brandenburg. His grandfather had bought it after he had become a little rich by building a brick factory. The Storkow Canal connected the estate via the lake-rich region of the Berlin Urstromtal with the nearby, up-and-coming capital of the German Reich. There, the bricks were urgently needed for building houses. Because the brickworks had helped the town to create jobs, the Aschers were valued. Paul Ascher grew up with his sister on the estate, which had since become the property of his father Paul. Two other sisters had died in childhood. Paul Ascher attended the small village school, but had difficulty in class, especially the subject of Latin at the grammar school, and so his parents received many admonishing letters from his teachers. When his mother died, his father sold the estate and moved to Berlin with his children. Soon after, his father died too, and so their uncle Karl, his father's brother, took care of the two children. Karl Ascher was an admiral in the Imperial Navy and lived in Kiel. The boy from the Brandenburg province was fascinated by the impressions he gained from his uncle in Kiel. He was fascinated by the navy and so decided to become a naval officer.

The First World War had already been raging for three years when Paul Ascher applied to serve in the Imperial Navy as an officer candidate straight after graduating from high school in Berlin at the age of 17 and a half. His officer career began with basic training with Crew VII/17 in July 1917. Paul Ascher was trained at the naval academy and on board the protected cruiser and training ship SMS Freya until December of that year. The young officer cadet then spent six months on the dreadnought battleship SMS Kaiserin. Further courses and training followed until the end of the war. Paul Ascher had found his calling in the navy; he enjoyed his service and performed well. When the war ended in 1918, his officer training was not yet complete, but the young midshipman managed to transfer to the new German Reichsmarine, where he was able to continue his career successfully. He also developed a great passion for sailing, took part in regattas and was considered the best sailor in the navy for a long time. In 1936, when asked about taking part in the Olympics, which were held in Berlin that year, he declined, saying that he felt he was too old and wanted to leave the field to younger people. The fact that this rejection was a sign of false modesty is demonstrated by his regatta victory at the North German Regatta Association during the Kiel Week in the same year. Even today, the many silver trophies he won testify to his successes at that time. Paul Ascher also had another habit associated with sailing, as his crewmate Edert remembered. When they were out together, Paul Ascher would ask about the sailors who were currently in custody and ask them to describe their offenses. If he found the offense to be less serious or even unjustified, he would ensure that the punished sailor was sent to his sailing boat as a sailing cadet and thus avoid custody at least temporarily. He himself had once contradicted a superior as a young officer candidate and, although he had been in the right, had to serve a sentence in custody.

The First World War had already been raging for three years when Paul Ascher applied to serve in the Imperial Navy as an officer candidate straight after graduating from high school in Berlin at the age of 17 and a half. His officer career began with basic training with Crew VII/17 in July 1917. Paul Ascher was trained at the naval academy and on board the protected cruiser and training ship SMS Freya until December of that year. The young officer cadet then spent six months on the dreadnought battleship SMS Kaiserin. Further courses and training followed until the end of the war. Paul Ascher had found his calling in the navy; he enjoyed his service and performed well. When the war ended in 1918, his officer training was not yet complete, but the young midshipman managed to transfer to the new German Reichsmarine, where he was able to continue his career successfully. He also developed a great passion for sailing, took part in regattas and was considered the best sailor in the navy for a long time. In 1936, when asked about taking part in the Olympics, which were held in Berlin that year, he declined, saying that he felt he was too old and wanted to leave the field to younger people. The fact that this rejection was a sign of false modesty is demonstrated by his regatta victory at the North German Regatta Association during the Kiel Week in the same year. Even today, the many silver trophies he won testify to his successes at that time. Paul Ascher also had another habit associated with sailing, as his crewmate Edert remembered. When they were out together, Paul Ascher would ask about the sailors who were currently in custody and ask them to describe their offenses. If he found the offense to be less serious or even unjustified, he would ensure that the punished sailor was sent to his sailing boat as a sailing cadet and thus avoid custody at least temporarily. He himself had once contradicted a superior as a young officer candidate and, although he had been in the right, had to serve a sentence in custody.

|

|

|

Torpedo boat Falke

Layed down: |

17.11.1925 |

Launch: |

22.09.1926 |

Commission: |

15.08.1927 |

End: |

14.06.1944

(sunk) |

Displacement: |

1.290 ts |

Size: |

88 m x 8 m |

Crew: |

120 men |

|

The Falke was first deployed during the Spanish Civil War. At the start of the Second World War, mine-laying and escort missions followed. The Falke operated in the North and Baltic Seas, as well as off the French coast. After several missions against the Allied landing forces, the Falke sank after being hit by bombs on 14 June 1944 in Le Havre.

|

In the mid-1920s, Paul Ascher was stationed in East Prussia. The daughters of the surrounding estates were invited to the naval festivals and that is how he met his future wife Ursula. The girl, who was four and a half years younger than him, came from a good family, a long-established East Prussian estate family called Dawert. On September 26, 1926 - Paul Ascher was on the staff of the Baltic Sea naval station at the time - the two married in the garden of the manor house. Three years later, in December 1929, their son Gert was born in Swinemünde. The small family followed their father on almost every change of command. They never really felt at home anywhere and Gert Ascher, who attended twelve different schools before graduating, had a hard time making friends. The father was usually not at home, which made the time when he was all the more precious. Many naval families shared this fate and so there was a strong bond at least among the naval officers' wives. Paul Ascher's career continued to progress. In September 1930, having been promoted to lieutenant, he was given command of his own boat for the first time. As commander, he commanded the torpedo boat Falke for two years.

When the National Socialists seized power, Paul Ascher's situation changed, as he had Jewish ancestors on both his father's and mother's side. In 1935, the Nuremberg Race Laws classified him as a so-called "Mischling 1st degree" or "half-Jew", which in the racial madness of the National Socialists meant that one parent or two grandparents were Jewish. Faith itself - Paul Ascher's family was Protestant - played no role. But as an officer who had been awarded the War Merit Cross 2nd Class and had served in the Reichsmarine, Paul Ascher did not fit the pattern of racial madness. He applied for an exemption, the so-called "Declaration of German Blood," which would put him on an equal footing with the "German Blood." Hitler had reserved the right to make this exemption. To assess Paul Ascher, he used photos of profile and front views that were sent in, which were ultimately decisive in approving the application. In an internal memo that later became known, Hitler perfidiously noted, "To be reviewed after the final victory." Of the more than 10,000 applications, only 260 were approved by 1941. Paul Ascher was very lucky. One can only imagine the severe humiliation he must have felt.

|

|

|

Panzerschiff Admiral Graf Spee

Layed down: |

25.06.1931 |

Launch: |

01.10.1932 |

Commission: |

06.01.1936 |

End: |

17.12.1939 (scuttled) |

Displacement: |

12.300 ts |

Size: |

186 m x 22 m |

Crew: |

1.150 men |

|

The Admiral Graf Spee was the last of the three Panzerschiffs built under the restrictions of the Treaty of Versailles according to the motto "faster than the stronger and stronger than the faster". She was first used as a fleet flagship from 1936 to 1937 during the Spanish Civil War. When the Second World War began, the Admiral Graf Spee was already in the South Atlantic as a precautionary measure and took part in the trade war in changing operational areas. The large cruising range allowed her to operate over a wide area from the east coast of South America to the Indian Ocean. On December 13, 1939, the Panzerschiff was involved in a battle with three british cruisers off the Rio de la Plata and suffered severe damage, forcing it to enter in Montevideo for repairs. Uruguay issued an ultimatum to the ship. Since the seaworthiness of the Admiral Graf Spee had not been restored during this time and the commander believed he was facing superior enemy forces, he scuttled his ship himself on December 17, saving the lives of many German and British sailors.

|

From March 1938, Paul Ascher, now with the rank of lieutenant-commander, served as first artillery officer on the Panzerschiff Admiral Graf Spee. The ship had just returned to Kiel from its fifth and final deployment in the Spanish Civil War. At the end of June he took the ship on a trip to the north. This was followed by the large fleet parade in Kiel on the occasion of the launch of the Prinz Eugen, as well as the autumn maneuvers as the fleet flagship. The Admiral Graf Spee then began a shipyard overhaul. During this time the ship was equipped with 10.5 cm anti-aircraft guns and new radio measuring equipment. The ship went into the Atlantic for testing for half of October and again in November. During the two trips, ports in Spain, Portugal and Morocco were called at. From March 22 to 24, 1939, Paul Ascher experienced the annexation of the Memel region to the Reich on board the Admiral Graf Spee, the command ship of all participating naval units at the time. This was followed by a large-scale maneuver in the Atlantic, in which, in addition to the three Panzerschiffs, the cruisers Leipzig and Köln, destroyers and three submarine flotillas also took part. After returning from this demonstration of power, the Admiral Graf Spee received the Legion Condor returning from Spain and escorted it to Hamburg.

From March 1938, Paul Ascher, now with the rank of lieutenant-commander, served as first artillery officer on the Panzerschiff Admiral Graf Spee. The ship had just returned to Kiel from its fifth and final deployment in the Spanish Civil War. At the end of June he took the ship on a trip to the north. This was followed by the large fleet parade in Kiel on the occasion of the launch of the Prinz Eugen, as well as the autumn maneuvers as the fleet flagship. The Admiral Graf Spee then began a shipyard overhaul. During this time the ship was equipped with 10.5 cm anti-aircraft guns and new radio measuring equipment. The ship went into the Atlantic for testing for half of October and again in November. During the two trips, ports in Spain, Portugal and Morocco were called at. From March 22 to 24, 1939, Paul Ascher experienced the annexation of the Memel region to the Reich on board the Admiral Graf Spee, the command ship of all participating naval units at the time. This was followed by a large-scale maneuver in the Atlantic, in which, in addition to the three Panzerschiffs, the cruisers Leipzig and Köln, destroyers and three submarine flotillas also took part. After returning from this demonstration of power, the Admiral Graf Spee received the Legion Condor returning from Spain and escorted it to Hamburg.

On August 21, 1939, the Admiral Graf Spee, equipped as a precaution for the trade war, left Wilhelmshaven to take up a waiting position in the South Atlantic. One month after she set sail - the Second World War had already begun three weeks earlier - the operational order was transmitted. In his position as First Artillery Officer, Paul Ascher had prepared well for war that had now arisen during the one and a half years on board. He knew his ship and the performance of his artillery. Supported by the supply ship Altmark, the Admiral Graf Spee independently waged cruiser warfare against Allied merchant shipping. The first victim of this operation was the British freighter Clement, which was sunk off the Brazilian coast on September 30th 1939. Four more merchant ships fell victim to the ship on the Cape Town-Freetown route. The area of operations was then moved to the Indian Ocean. The empty coastal tanker Africa Shell was sunk here on November 15th. Back in the old area of operations, the Admiral Graf Spee sank three more merchant ships. On December 5th, Paul Ascher and the first officer were awarded the Iron Cross 1st Class by the commander for the successful sinking. The total of nine ships sunk had a tonnage of 50,000 gross register tons. Great importance was attached to compliance with the prize regulations. The ships were initially ordered to stop and to maintain strict radio silence. Before the sinking, the crew was given sufficient time to leave the ship, so that not a single fatality occurred. The shipwrecked people were then taken on board the Admiral Graf Spee. While the officers remained on board, the crew were handed over to the supply ship Altmark.

On August 21, 1939, the Admiral Graf Spee, equipped as a precaution for the trade war, left Wilhelmshaven to take up a waiting position in the South Atlantic. One month after she set sail - the Second World War had already begun three weeks earlier - the operational order was transmitted. In his position as First Artillery Officer, Paul Ascher had prepared well for war that had now arisen during the one and a half years on board. He knew his ship and the performance of his artillery. Supported by the supply ship Altmark, the Admiral Graf Spee independently waged cruiser warfare against Allied merchant shipping. The first victim of this operation was the British freighter Clement, which was sunk off the Brazilian coast on September 30th 1939. Four more merchant ships fell victim to the ship on the Cape Town-Freetown route. The area of operations was then moved to the Indian Ocean. The empty coastal tanker Africa Shell was sunk here on November 15th. Back in the old area of operations, the Admiral Graf Spee sank three more merchant ships. On December 5th, Paul Ascher and the first officer were awarded the Iron Cross 1st Class by the commander for the successful sinking. The total of nine ships sunk had a tonnage of 50,000 gross register tons. Great importance was attached to compliance with the prize regulations. The ships were initially ordered to stop and to maintain strict radio silence. Before the sinking, the crew was given sufficient time to leave the ship, so that not a single fatality occurred. The shipwrecked people were then taken on board the Admiral Graf Spee. While the officers remained on board, the crew were handed over to the supply ship Altmark.

In the meantime, December had begun and the operation was nearing its end. Before the return journey, the commander, Captain Langsdorff, wanted to search the east coast of South America for Allied merchant ships. On December 13, 1939, however, his ship encountered an Allied warship force off the mouth of the Rio de la Plata, consisting of the British cruisers HMS Exeter and HMS Ajax, as well as the New Zealand cruiser HMNZS Achilles. A battle ensued. Paul Ascher successfully directed the artillery deployment of his ship. The HMS Exeter was badly damaged and had to abandon the battle, while the other two cruisers were slightly damaged. The Admiral Graf Spee also suffered a number of hits, causing considerable damage. After the battle, 36 people were killed and 59 wounded on board. The most serious hit was in the forecastle, which seriously called into question the ship's seaworthiness, particularly in view of the winter conditions in the North Atlantic. Because the ship could not be made ready for the return journey home using on-board equipment, the commander decided to enter the mouth of the La Plata, even at the risk of being trapped there. The naval command gave its consent to this.

A few hours later, the Admiral Graf Spee dropped anchor off Montevideo, in the territorial waters of the neutral country of Uruguay, and requested a reasonable period of time to restore seaworthiness. However, the Uruguayan government issued a seventy-two-hour ultimatum. The ship was to leave port by the end of the ultimatum or it would be interned. Further negotiations, in which Paul Ascher was also involved, could not change this. There was not enough time for repairs. The Royal Navy sent additional troops to the mouth of the La Plata and, by skillfully manipulating reports, created the impression that the first heavy units had already arrived and that a breakout of the German ship would inevitably result in its destruction. In this seemingly hopeless situation, Captain Langsdorff, in agreement with the Naval Command, decided to scuttle his ship.

The Admiral Graf Spee set off on its last voyage on the evening of December 17, 1939. Outside Uruguayan territorial waters, after the demolition crew still on board, including Paul Ascher, had left, all of the remaining ammunition was detonated. The wreck burned for two days before the Admiral Graf Spee sank. In a speech to the crew, the commander announced that they would now be interned in Argentina. He was happy that he now knew that his proven, brave crew was safe, that Argentina was giving the Spee men a warm welcome and that their fate was in good hands, not least with the large German colony. He also explained his decision to blow up the ship to protect his crew and his ship from enemy hands. In the evening, Langsdorff sat with some officers and local Germans. At around 10 p.m. he said goodbye to the officers with a firm handshake, spoke a few words to each of them and retired to his room, where he took his own life.

|

|

At the funeral of Captain Langsdorff after his suicide, Paul Ascher carried the medal cushion |

|

|

Photo Gallery – The End of the Battleship Admiral Graf Spee

Click on the pictures to enlarge.

The sympathy at his funeral three days later was enormous. Paul Ascher, along with three other officers, walked in front of the coffin, carrying his commander's medal cushion. The two had not only been on a professional but also friendly basis, which made the farewell all the more difficult. After the funeral, internment in Argentina began. Most of the crew members remained in Argentina until the end of the war and some even beyond. Paul Ascher, on the other hand, decided to return home. Despite his difficult situation as a "half-Jew", he dared to undertake the adventurous undertaking. He was surely motivated by the desire to return home to his family. With the help of a German-Argentinian family, he escaped from internment and made it to Spain hidden in a mail plane. In the spring of 1940, he finally reached his family in Berlin. Back in the Navy, he was initially placed under special command of the Naval High Command North until a new command was found in May. Paul Ascher remained in staff service. Thanks to his special permission, he was spared from a decree issued by the High Command of the Wehrmacht at this time, which stipulated the dismissal of all "Mischlinge 1. Grades" from the Wehrmacht.

From May to July 1940, Paul Ascher served as First Admiral Staff Officer in the staff of the Commander of the Panzerschiffe. Since the Commander, Vice Admiral Marschall, was also the Fleet Commander, the staff work practically also related to that of the Fleet Command, to which Paul Ascher was transferred after the dissolution of the Staff of the Commander of the Panzerschiffe at the end of July 1940.

|

|

|

Battleship Gneisenau

Layed down: |

18.12.1934 |

Launch: |

08.12.1936 |

Commission: |

21.05.1938 |

End: |

01.07.1942

(scrapped) |

Displacement: |

35.000 ts |

Size: |

235 m x

30 m |

Crew: |

1.840 Men |

|

As the fleet flagship, the Gneisenau took part in a number of offensive operations from the beginning of the war, together with her sister ship Scharnhorst. After an extensive operation in the Atlantic, both ships were stuck in Brest, France, from April 1941 to February 1942 after being hit by multiple bombs. Shortly after the retreat via the English Channel, the Gneisenau was hit by a fatal bomb, which ignited the powder chamber of Turret Anton. The ship was then taken out of service for repairs and reconstruction work, which was stopped at the beginning of 1943 on Hitler's orders.

|

At the beginning of June, Paul Ascher and the fleet staff boarded the battleship Gneisenau. The High Command of the Navy was planning an advance to relieve the pressure on Lieutenant General Dietl's units, which were still fighting at Narvik. At this point, the High Command of the Navy was completely unaware that the unit would find itself in the middle of a retreating British force. On 4 June, the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Admiral Hipper set sail, accompanied by four destroyers. While the approach was still underway, the empty troop transport Orama, the tanker Oilpioneer and the trawler Juniper were sunk on 8 June. Three hours after the Admiral Hipper and the destroyers were detached for refuelling in Trondheim, a plume of smoke was sighted on the horizon from the Scharnhorst. The contact soon turned out to be the British aircraft carrier HMS Glorious with its destroyer escort.

The aircraft carrier was completely unprepared for the attack. None of the aircraft were on the flight deck at the time or in the air. The engine was travelling at 17 knots with not all boilers running. Even the crow's nest was unoccupied. While the destroyers were covering the aircraft carrier with smoke, the carrier tried to escape and launch aircraft. But the third salvo from the Scharnhorst prevented any aircraft from launching. After almost two hours of fighting, both of the escort destroyers and the HMS Glorious itself were destroyed. Only 46 survivors were later rescued from the water by Norwegian ships and a German aircraft. The German ships made no rescue attempts due to the risk of being discovered. The Scharnhorst had to endure a heavy torpedo hit in the stern during the battle. Otherwise, the damage to the German ships was rather minor. The operation ended after this battle. Despite the success, the actual aim of the operational order (the relief of Lieutenant General Dietl's troops), which in the eyes of the fleet commander had rightly lost its importance due to the changed situation, was missed. This point led to such quarrels between the fleet commander and the commander-in-chief of the Navy that Vice Admiral Marschall was finally replaced as fleet commander by Vice Admiral Lütjens.

The aircraft carrier was completely unprepared for the attack. None of the aircraft were on the flight deck at the time or in the air. The engine was travelling at 17 knots with not all boilers running. Even the crow's nest was unoccupied. While the destroyers were covering the aircraft carrier with smoke, the carrier tried to escape and launch aircraft. But the third salvo from the Scharnhorst prevented any aircraft from launching. After almost two hours of fighting, both of the escort destroyers and the HMS Glorious itself were destroyed. Only 46 survivors were later rescued from the water by Norwegian ships and a German aircraft. The German ships made no rescue attempts due to the risk of being discovered. The Scharnhorst had to endure a heavy torpedo hit in the stern during the battle. Otherwise, the damage to the German ships was rather minor. The operation ended after this battle. Despite the success, the actual aim of the operational order (the relief of Lieutenant General Dietl's troops), which in the eyes of the fleet commander had rightly lost its importance due to the changed situation, was missed. This point led to such quarrels between the fleet commander and the commander-in-chief of the Navy that Vice Admiral Marschall was finally replaced as fleet commander by Vice Admiral Lütjens.

With the new fleet commander (still acting as deputy), Paul Ascher undertook another attack with the Gneisenau on 20 June against English ships. However, the operation ended as soon as the ship left the Norwegian archipelago, when the Gneisenau was hit by a torpedo from the British submarine HMS Clyde which was lurking there.

With the new fleet commander (still acting as deputy), Paul Ascher undertook another attack with the Gneisenau on 20 June against English ships. However, the operation ended as soon as the ship left the Norwegian archipelago, when the Gneisenau was hit by a torpedo from the British submarine HMS Clyde which was lurking there.

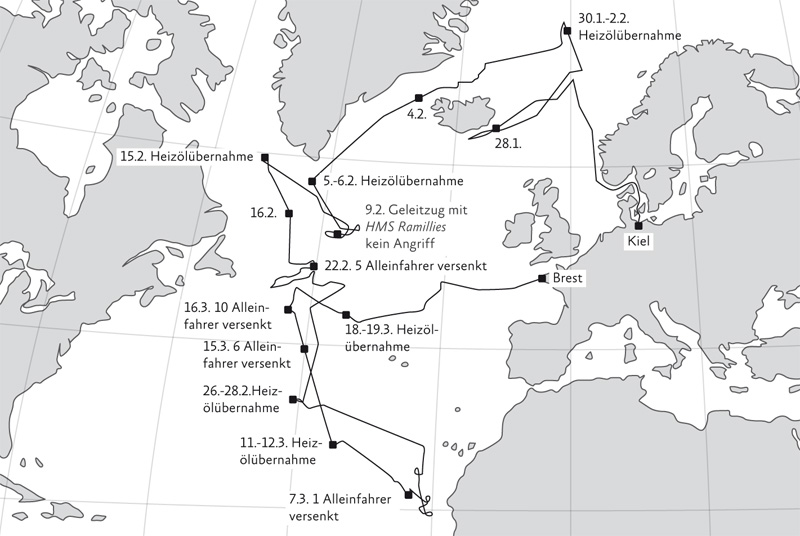

At the end of July 1940, as already mentioned, the staff of the commander of the Panzerschiffe was disbanded and Paul Ascher joined the fleet staff as First Admiral Staff Officer, where he had already been working. After all repair work on the two battleships Gneisenau and Scharnhorst had been completed, Paul Ascher embarked again with the fleet staff on the Gneisenau in December 1940. The fleet planned to use the two ships to advance into the Atlantic in order to operate against the Allied shipping convoys. The operation was given the name "Berlin". However, storm damage to the Gneisenau forced the first breakout attempt to be aborted on December 28, 1940. The second attempt, a month later, also had to be aborted when the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau encountered two British cruisers. At the beginning of February 1941, the unnoticed breakthrough into the Atlantic was finally achieved. Admiral Lütjens now concentrated on the convoys on the North Atlantic route, which ran from Canada to Great Britain. On February 9, a convoy was sighted for the first time. But the initial joy quickly faded when the battleship HMS Ramilies was identified as the escort vessel. The operational order strictly prohibited the initiation of battles with equal opponents and so the convoy remained untouched.

After a long, unsuccessful search, a convoy was not sighted again until February 22nd. However, this convoy was on its way back to America and unloaded, and therefore not an ideal target. Admiral Lütjens decided to attack anyway and sank five ships. On March 7th, another convoy was discovered, but as it was accompanied by the battleship HMS Malaya, an attack was not launched. Instead, the two battleships holded contact and guided two of their own submarines to the convoy. Six ships were sunk the very next day. The search continued. Together with the supply ships Uckermark and Ermland, the fleet formed a search strip that covered a distance of 220 km. Six individual vessels were the first to fall victim to the fleet. Then, on 15 March, the Uckermark sighted a large group of unsecured ships. Three tankers were captured as prizes and sent on their way to occupied France, but only one of them reached the port. Four more tankers were sunk. During the night, another convoy was sighted and attacked at dawn. Ten ships fell victim to the Gneisenau and Scharnhorst. Then the battleship HMS Rodney approached and forced the German fleet to retreat. It was the last action of Operation "Berlin". On the morning of 19 March, the two ships set course for Brest, where they arrived three days later. The next operation of the Gneisenau and Scharnhorst was planned together with the battleship Bismarck and the cruiser Prinz Eugen, but this never happened.

After a long, unsuccessful search, a convoy was not sighted again until February 22nd. However, this convoy was on its way back to America and unloaded, and therefore not an ideal target. Admiral Lütjens decided to attack anyway and sank five ships. On March 7th, another convoy was discovered, but as it was accompanied by the battleship HMS Malaya, an attack was not launched. Instead, the two battleships holded contact and guided two of their own submarines to the convoy. Six ships were sunk the very next day. The search continued. Together with the supply ships Uckermark and Ermland, the fleet formed a search strip that covered a distance of 220 km. Six individual vessels were the first to fall victim to the fleet. Then, on 15 March, the Uckermark sighted a large group of unsecured ships. Three tankers were captured as prizes and sent on their way to occupied France, but only one of them reached the port. Four more tankers were sunk. During the night, another convoy was sighted and attacked at dawn. Ten ships fell victim to the Gneisenau and Scharnhorst. Then the battleship HMS Rodney approached and forced the German fleet to retreat. It was the last action of Operation "Berlin". On the morning of 19 March, the two ships set course for Brest, where they arrived three days later. The next operation of the Gneisenau and Scharnhorst was planned together with the battleship Bismarck and the cruiser Prinz Eugen, but this never happened.

|

|

Operation "Berlin" |

|

|

On March 27, 1941, Paul Ascher returned to Kiel with the fleet staff and its sub-staff, where the staff initially took up quarters on the battleship Schleswig-Holstein. The time passed with meetings to plan the next operation. During this time, the Gneisenau was hit heavily by bombs in Brest, which rendered the ship inoperable for months. At the end of April, the fleet staff transferred to the fleet tender Hela and was transferred from Kiel to Swinemünde and finally on to Gotenhafen. There, on May 1, news arrived that Hitler was planning a visit to the Bismarck and Tirpitz on May 5. One day before this event, the fleet commander sent his First Admiral Staff Officer, Paul Ascher, to the fortress command of Gotenhafen to discuss the visit program. He did so, but did not accompany the subsequent visit.

|

|

|

Paul Ascher's chamber on

the Bismarck

(Upper deck, Dept. VIII StB)

1 |

Bed |

2 |

Bookcase |

3 |

Bathroom sink |

4 |

Desk |

5 |

Air Condition |

6 |

Radiators |

7 |

Portholes |

|

On May 12th, the fleet staff embarked on the battleship Bismarck for the first time to take part in an readiness exercise, followed by a battle exercise the next day. On board, almost the entire aft superstructure was available to the staff as living, working and meeting space. Paul Ascher's single cabin was on the upper deck on the starboard side, directly opposite the Asto office. It was a very spacious cabin considering the lack of space on board a warship. This was initially a short stay. The next day they returned to the Hela. On May 15th, Paul Ascher accompanied the fleet commander on his flight to Berlin. The last meeting with the naval command took place there before departure. He probably also found the opportunity to say goodbye to his heavily pregnant wife. Three days later, the time had come: Operation "Rheinübung" began. The survivor and then IV Artillery Officer of the Bismarck, Burkard Freiherr von Müllenheim-Rechberg, met the fleet commander, accompanied by his First Admiral Staff Officer Paul Ascher, on the morning of May 27th. It was the last time that both were seen. The 41-year-old family man Paul Ascher was killed in the battle that followed shortly afterwards.

Paul Ascher's wife Ursula was at her sister's in Insterburg in East Prussia with her twelve-year-old son Gert, so that she would not be alone when her second child was born. There she learned of the sinking of the Bismarck and was immediately certain that her husband had gone down with the ship. This time Paul Ascher had not taken his wedding ring with him on the trip as he usually did. Perhaps he had a premonition, or perhaps it was just an oversight. Seven weeks after his death, Paul Ascher's daughter Monika was born on July 9, 1941. She grew up without ever having met her father. Nevertheless, her father, unknown to her, was always present and was loved and missed by his wife, son and daughter for their entire lives.

|

|

|

* She was convinced that her husband, as an experienced artilleryman, was deployed in the artillery during the battle despite being on the staff and fell into the artillery control posts when the early hits were made.

|

Paul Ascher's widow bore her husband's death with great bravery and dignity. She found consolation in the birth of their daughter Monika and the knowledge that her husband had been killed quickly.* She deliberately did not have the then usual phrase "for Führer and Fatherland" printed in the obituary. Over the years she maintained contact with her husband's former naval friends and kept his memory alive, as did the rest of her family. One of Paul Ascher's crewmates spoke highly of him, saying that he was the most decent, clever and lovable comrade and friend.

Paul Ascher was posthumously promoted to captain.

|

|

|